Blog

The mysterious case of the pamphlet

Monday 17th April 2023

Candlestick Press

Here at Candlestick we call our small anthologies pamphlets. Pamphlets are relatively common creatures in the poetry world, and are generally understood to be a publication that is half the length (or less) of a full collection. Poets often publish a pamphlet as their first work.

Despite this, it’s a description that sometimes surprises our readers – which is why we thought we’d venture on this brief excursion into the history of a word that (it transpires) dates all the way back to the ancient Greeks.

In Greek pamphilos signifies “loved by all” from pan– “all” and philos “loving”. This is probably why in the 12th century a pamphlet became “a short love poem written in Latin”.

These meanings are far removed from contemporary usage, which is more likely to contain ideas of information and usefulness. Indeed, the Cambridge Dictionary Online provides the rather prosaic definition: “a thin book with only a few pages that gives information or an opinion about something”. The Oxford Online Dictionary grants a little more weight by referring to “a small booklet or leaflet containing information or arguments about a single subject”.

In between times, pamphlets have often been political: a way of making your voice heard and trying to persuade people to agree with you. “Pamphleteering” was a radical activity with thinkers as diverse as Martin Luther, George Bernard Shaw and Beatrice Webb dipping their toes into the water. So far, so very factual – and, in fact, rather unpoetic.

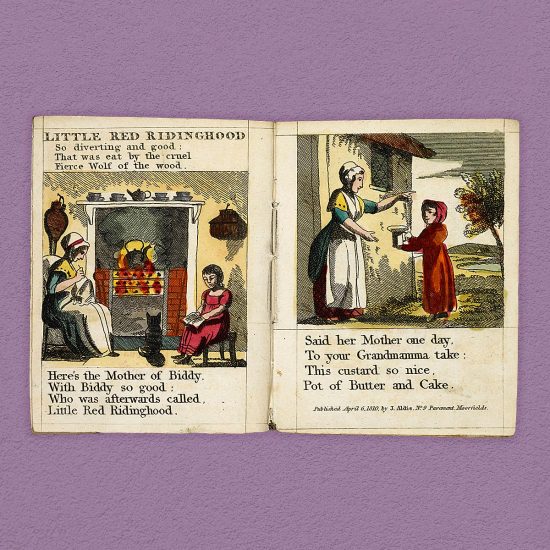

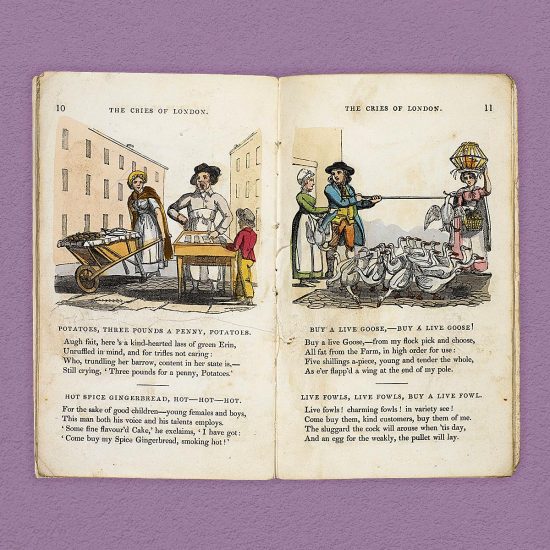

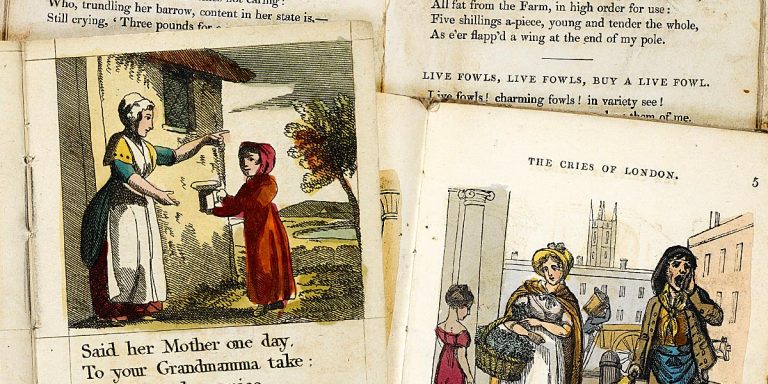

Google pamphlet and it’s often the word chapbook that pops up as a synonym. In Victorian times and even earlier, chapbooks were charming little books containing anything from riddles and short biographies to tales of travel and prayers. They were sold by travelling “chapmen” (“chap” being the Old English word for “trade”) who counted all manner of bits and bobs (bootlaces, buckles, whistles etc.) among their wares.

The small size of a chapbook which might be only a couple of inches tall ensured they were cheap to make and buy, and would appeal to poorer readers whose literacy skills might be rudimentary. At the same time, publishers also had an eye on a more affluent market, and would sometimes add a card or coloured-paper cover or hand-coloured illustrations. Embellishments like these might double the price – a common phrase was “penny plain, twopence coloured”.

Producing chapbooks was something of a cottage industry as they were usually hand-printed on manual presses and any folding, stitching, trimming etc. had to be done by hand. This kind of work was often carried out by women, with children often used for colouring in the illustrations.

Chapbooks eventually fell from favour but not before briefly evolving into “penny dreadfuls” and later into children’s comics.

Chapbook/pamphlet; the words are used interchangeably in the world of poetry. It’s strange that the OED doesn’t have a listing for the pamphlet as a poetry booklet whereas a chapbook is described as “ a small paper-covered booklet, typically containing poems or fiction.”

What we do know is that the chapbook’s artisan beginnings are still reflected in the attention to detail (and beauty) that characterises many contemporary versions. We also know that the pamphlet’s history as a vehicle for influencing thinking means it has a reputation for seriousness. A pamphlet is certainly not a leaflet – something that can be readily thrown away.

And snuggled somewhere inside that word is still the old meaning of loved by all. We hope this might be the effect of our own small anthologies as they fly out into the world.